- Poetry School

- Posts

- Volume 5, No. 13: Welcome, Darkness

Volume 5, No. 13: Welcome, Darkness

good news, divined questions, sniffing twigs, coming alive for winter

Greetings, poetry pals. I tried something new with the newsletter this week. I started a note on my phone where I collected thoughts and ideas as I had them. Then, in little bits of time—20 minutes here, 30 minutes there—I wrote what you are now reading in pieces, transferring and translating the notes as I went. Reader, it has been a joy. This is how my brain actually works. I don’t know why I’ve been trying to get myself to write newsletters in one go. I know better than to make promises, but I think we’re onto something. Next week, look out.

Here’s a not-at-all-secret fact about me: I care deeply, and generally, about people. People being able to afford food and shelter and having access to health care. People not being kidnapped by ICE. Etc. So, obviously, I am feeling pretty goddam excited for New York City this week. Like all of you, I am celebrating the election of Zohran Mamdani in a big way. This is a big win that a lot of people worked really hard to make happen! This is a big cause for celebration! I especially love this reminder from Margaret Killjoy and this photo of Mamdani at a rally for trans youth in February. There was no election in my tiny town (population 734) this week, but wow did it feel great to be able to do a little hope scrolling on Tuesday night.

A few other good things:

Thank you to everyone who has donated to my 30 Poems in November! fundraiser. I appreciate it so much. My goal is to raise $500 this month; even donating $1 makes a big difference! You can read the poem I wrote on November 1st, “17 (Un)lectures on Being In” below. If anything in it moves you, it would mean a lot to me if you made a donation or shared my fundraising page with a friend.

My dear friend Emma just started a newsletter called Creation as Hope. It’s a “compendium of inspiration and imagination and connection and care” and you can read the first issue here. You should subscribe because Emma is rad and thoughtful and has a lot to say about poetry and creation and connection and also there are beautiful pictures of dahlias (you’re welcome).

Notes On...

Welcome, Darkness

Those of you who have been around for a while know that my time is now. I revel in the return to standard time. I love this season of darkness. I love it deeply and wildly, with every molecule of my being. December is my favorite month, followed closely by November. We are on the cusp of entering the Season of Light. This is the season when I come alive. I know it is so hard for so many of you, and I can't change that. But I would like to be a candle. I would like to share as much of my winter aliveness as I can.

Earlier this week, I sat on my porch as the sun set, working on a poem. I stayed there into the dusk. That transition moved through me. What a miracle to experience it. The light and the dark following and all the infinite shades between. I have words and care and awe to give away this season. So I’d love to know: what would help? Would you like to hear about my winter rituals? Poems celebrating the dark? How can I be a candle for you in my writing these last two months of the year?

I’m genuinely asking! Feel free to reply or leave a comment. I’m ready to share the joys of the darkness in this newsletter in the coming weeks.

Voice Notes & the Lineage of Letters

Last weekend I had lunch with my aunts, and I told them all about voice notes. Voice notes are a big deal in my world; they have profoundly changed my life this year. I was explaining to my aunts how I use them and why I love them, and my aunt said that voice notes sounded like “vocal letters.”

This is the best description of voice notes I’ve heard yet! Like letters, they are intimate and asynchronous. Because they are not live, they invite a certain kind of deep listening—at least for me. Like any form of communication, they are not for everyone, and they are not everything. There are kinds of connection I experience when I’m talking with someone in person or even over the phone that I do not experience in a voice note. And, also, there are kinds of connection I experience sending and receiving voice notes that I do not experience in live conversation.

I shared my aunt’s reflection with a long-distance friend, someone I talk with almost exclusively in voice notes. She made the insightful observation that both letters and voice notes are embodied in ways that other forms of asynchronous communication aren’t. In a voice note, you hear someone’s actual voice. In a letter, you see their actual handwriting.

At the very beginning of email, I used to correspond with people electronically, exchanging long emails with long-distance friends. I remember there was a certain amount of discourse about the death of letter-writing, and whether or not email could ever take its place. I don’t correspond with anyone via email anymore; that practice lasted a few years, maybe. Now I think it has to do with embodiment. Text is disembodied. Voice notes carry the lineage of letters.

A lot of people these days like to criticize the internet, and especially internet friendships. People talk about online friends and “in real life” friends (you will never hear me use this phrase) as if the internet isn’t real life, as if genuine intimacy can only happen in one particular way, in one particular kind of room. It is true that the internet has birthed many terrible things. It is true that there is a kind of “connection” that happens on social media that is not genuine connection. But my voice note friendships (and even my long-distance text-based friendships) are not a new thing. For centuries, people engaged in lifelong, intimate correspondence with people they never met, or met rarely, in person. This is an old, old lineage. This is an ancient technology.

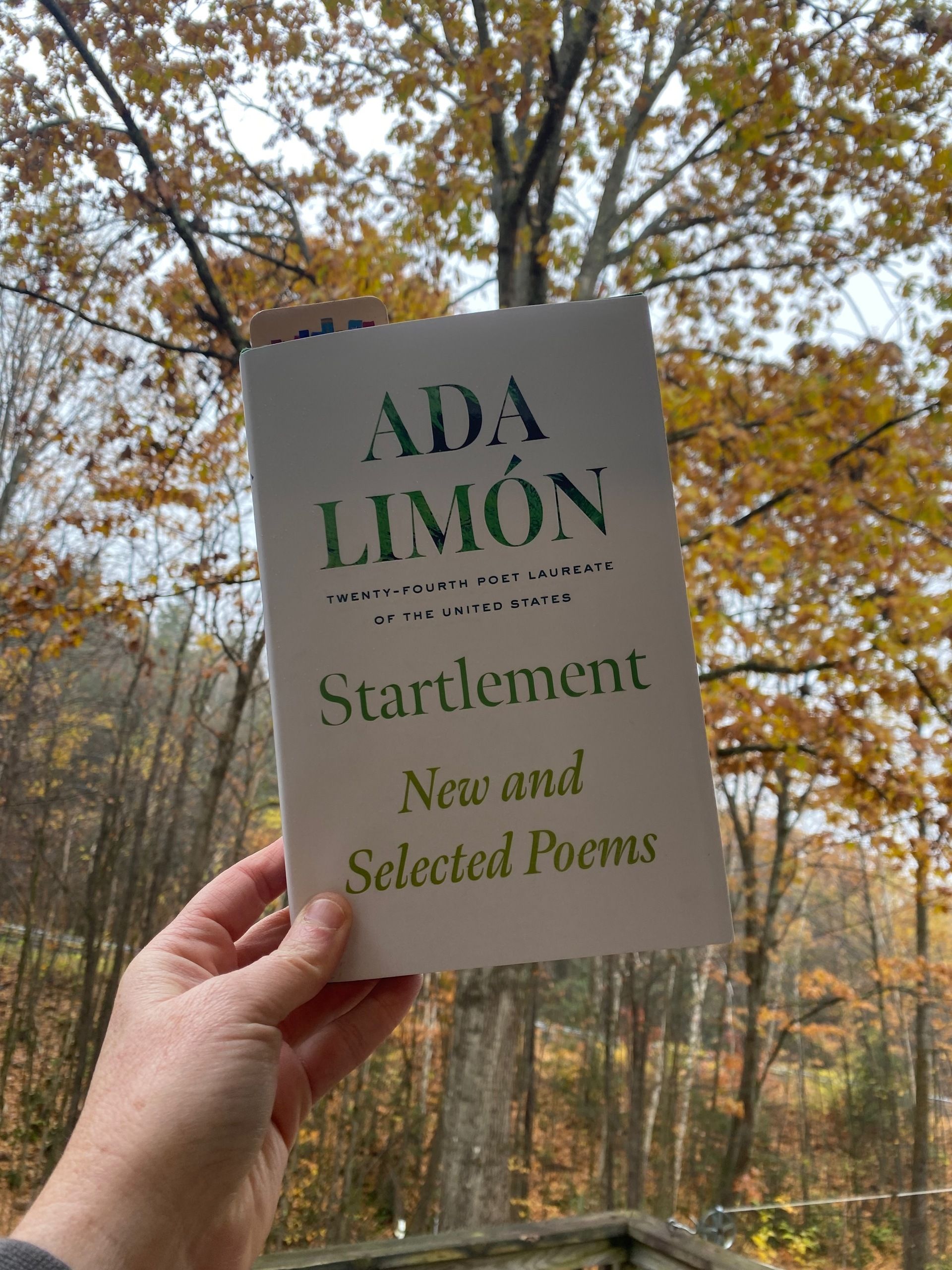

Swelling Into

I’m currently reading Ada Limón’s just-released new and selected, Startlement. I love getting to read a poet’s body of work across time like this. I don’t like her earlier work as much as her later work, but even in the selections from her first books, where I’m less wowed by every individual poem, there are lines that stun me, like this one from the poem “Miles per Hour”:

“each single thing / made me grab you harder, want to be connected / to something larger, as if we could swell into / the universe itself.”

I’ve been thinking a lot with water this past month (and always), and especially about all the ways water moves, and the words we use to try to describe that movement: swell, crash, break, flow, run, ripple, fall, wave, stream, pour. Some of these words, like stream, are both the name of a movement and the name of a being

East Branch Swift River in Petersham, MA

So I like thinking about swelling into the universe. Moving closer, like water, to everyone and everything I am connected to.

17 (Un)lectures On Being In

I’ve been writing a poem every day in November in support of the Center for New Americans (donate here!). I’m often hesitant to share poems I write here, for a reason I detest: because I am also trying to publish poems, and most magazines and journals will not publish anything that has been “previously published,” even in a blog, newsletter, or social media. I dislike a lot of things about publishing, and this is one. It is also true that getting published is not why I write. I share poems with friends all the time; I wouldn’t be a poet if I didn’t. I’m sharing this poem (likely not in its final form) with you in the spirit of abundance. I do not want to hoard poems. I want to give them away. Endless thanks and big love to the friends I think with and quote here, for being in with me.

Seventeen (Un)Lectures on Being In

1.

Water work is the work we do inside, but out in the open. Rain is born knowing how to sing. There’s no formula for falling.

2.

A friend tells me that when she was pregnant, it felt like “tapping into a deep well of ancestral wisdom.” In late February and early March, I walk by the taps on the sugar maples lining my road: tiny wells of sustenance. The ancient Japanese calendar includes 72 micro-seasons; depending on the year and its avalanche of weather, sapping season might coincide with mist starts to linger, hibernating insects surface, sparrows start to nest, and distant thunder.

3.

At a reading, Kenzie Allen says that every poem is secretly an ars poetica. She also says that every poem is secretly an elegy. I hold one of these statements like a net inside my chest; the other, like vapor disappearing.

4.

I have always wanted to stay. Many people I love have not always wanted to stay. “This poem is not the world,” says Mary, moonlit lamp of my life.

5.

I will not add my elegy to the shrine of the world. Already there is wind. Already the snow settling in the valleys.

6.

A friend tells me she’s been wondering whether “every poem is a research project.” If every poem is a research project, I am studying how to love. I am studying how to love even what leaves.

7.

For a time I lived on a hillside farm in Vermont; every morning I’d wake up and look out my bedroom window into the crown of an enormous cottonwood tree, its branches reaching and holding—light, wind, the traces of song, a dozen different bird languages. Nobody who lived in the presence of that tree was unchanged by it. But cottonwoods often cleave, and there was a dark fissure—a mortal wound—spreading and growing deep in the tree’s center, so two months ago, the stewards of that place, its keepers and speakers, made the decision to kill the cottonwood.

8.

A friend tells me, “trees create the world they want to live in, very, very slowly.” I am writing these words in the season of “light rains sometimes fall.” Tomorrow the season will become “maple leaves and ivy turn yellow,” but we are in a drought year—all of Massachusetts is experiencing “significant drought,” and my tiny town is bright orange on the state-issued map, “critical drought”—which brings brown leaves.

9.

The ancient Romans built their dizzying monuments to empire with concrete, which is why these built-stories have lasted for almost 2,000 years. Their concrete, which they made using a process called “hot mixing,” also included small chunks of calcium carbonate, called lime clasts, which they purposely left unmixed. When lime clasts are exposed to water—imagine rain sheeting over that architectural ode to violence, the Colosseum—a chemical reaction occurs that essentially re-makes the concrete, filling in cracks before they spread: self-healing concrete.

10.

I get an email inviting me to the ceremony the keepers and speakers of the land are holding for the cottonwood tree. Speaking about the tree, Helen, whom I have not seen in almost twenty years, but who taught me about gentleness and care when I was twenty-two and living on her farm, writes: “It’s an ancient being,” and “To take a tree down is an ending of stories,” and “This tree is our magnificent friend,” and “This tree is its own ecosystem.” What begins where stories end?

11.

Already the long roots, the brown grasses. Already the fireflies. Already stone.

12.

Water work is the work of staying. An almanac of transformation. A friend makes a watercolor to go with a line of poetry I send her, a line about being held by many hands in a season of change, a watercolor of a person being held by water, and when I tell her how much I love it, she says, “one of the best sets of hands I can imagine.”

13.

A friend tells me she is thinking about the differences between “institutional knowledge” and “knowledge of the heart.” When I google “drought in Massachusetts” in order to locate the official term for the experience I see breaking the bodies of beeches and rivers, I click into a mass.gov webpage with a map of the damage, and am confronted with a banner warning that reads: “President XXX has frozen SNAP benefits for November 1. All residents who receive SNAP benefits will be impacted.” This, despite a judge ruling that the government must continue providing food assistance.

14.

The bodies we live inside are self-healing until they aren’t. There are some wounds even rivers cannot ease, some cracks even water cannot flow through. I can still feel the sun-made skin of the cottonwood pressing into my back as I leaned against its magnificent trunk in the early mornings: (un)knowledge of the heart, stitched in tones of what is untranslatable.

15.

A friend and I are rereading a favorite book together. She texts me she’s thinking about “art as diffusing, living outside the self, storing things outside oneself.” I cannot write separateness into a poem; the form rejects it.

16.

A friend tells me she’s been thinking about the word “being,” and how, if you remove the “g” it turns into “be in.”To be a being: to be in. Our bodies, borderless and made of water.

17.

A poem is a container for what my beloveds tell me. My favorite season is coming, season of darkness, season of the long evenings, season of the sharp wind blowing blue in the hills, season of flame flickering in windows, season of trees revealing their hidden music. I am a continent of what I miss.

Tree Talk: Two Branches

There are two branches I love, on two different trees I love, that I have been trying to describe for many years. Both branches are on sugar maples. One branch is on the tree I call “my tree,” although the possessive pronoun does make me a bit uneasy. The tree does not belong to me and did not choose me. The “my” is the best I can do, for now, to express care and responsibility: I am in kinship with this being. I am trying to be.

The branch I love dances. It has curves and dips that move. I cannot describe it because it is not fixed in time or space. From every direction, it changes. Its shape and story, infinite.

The dancing branch is on this tree.

The other branch I love is on another sugar maple, this one on my drive to school. I have never taken a photo of it and probably never will. This branch is circular. It makes a circle in the sky. I call it the circle branch, and yet, again—it moves. The circle breaks and reforms. In every season, its shape is different. On my way to school, I approach it from the north. On my way home from school, the south. It is a circle, then a loop, then a spiral, then a curve flowing into the sky.

It is wild to me that so many people think of trees as beings that do not move. In a branch, there are endless decisions. Branches are life histories, books of time. Trees move, just not in the way we’re used to thinking about movement.

A Very Good Thing: Klamath Dam Removal

A few friends have sent me news articles about the Klamath Dam removal project in the last few weeks. My friend Surabhi, who lives in Oregon, and with whom I spend a lot of time thinking about rivers, sent me this one:

The article begins with this sentence: “For the first time in more than 100 years, Chinook salmon have been spotted at the confluence of the Sprague and Williamson rivers in Chiloquin, the government seat of the Klamath Tribes in Southern Oregon.”

The removal of four dams on the Klamath River is the biggest river restoration project in U.S. history. There is so much that is so bad right now. But this is a good thing. This is a good, good thing.

Another friend sent me this article. I’d shared with her a poem I’d written about the Connecticut River—a river broken and broken and broken by dams. A few weeks ago, I had a conversation with a dear friend who’s involved in dam removal efforts on the Connecticut. He mentioned the sadness of never having experienced rapids on the river—it’s been so marred by dams that, for much of its run, it’s more like a series of connected lakes than a living river (though of course it is a living river, despite its wounds). Then I read this article about the future of the Klamath and its living, rushing waters:

The Klamath dam removal project was a massive, decades-long struggle led by the Klamath, Shasta, Yurok, Hoopa, and Karuk tribes. I have only just started reading about it in depth, and I cannot do so without crying. I am so deeply inspired by this powerful and steadfast organizing, by what is—what is!—possible. If you’re wondering why I’ve linked three separate articles about this (and I highly recommend the one below, as it includes links to lots of further reading), it’s because I want to make a really big deal about it. The river is still healing. There is so much more work to do. But this is a really big deal.

As Chandra LeGue says in this article: “This landscape still needs time to heal towards that vision, but if the Klamath dam removal project has taught us anything, it is that persistence over time does make a difference, and that this river, the landscape it flows through, the people who call it home, and the salmon and other wildlife that live here are remarkably resilient.”

Describing what it was like to hear water coming back through the canyon where it hadn’t flowed in 100 years, Sami Jo Difuntorum, cultural preservation officer for the Shasta Indian Nation, says: “What it said to me was the earth and the rocks were welcoming the water back. And so that meant healing.”

Local folks—if you’re looking to learn more about ongoing activism around dam removal on the Connecticut, the Connecticut River Defenders is a good place to start.

Sniffing Twigs: A Practice of Attention

This month I’m taking a class with Garth Greenwell on Confessions. I took a class with him a few years ago on Edinburgh, one of my favorite novels, and I find him to be such a thoughtful, generous teacher. I won’t get into all the fascinating things he has to say about Augustine, though you can read more about his lifelong project of reading Confessions here and here. I will just share this one thing, something Greenwell says animates much of what he’s trying to do with his writing, that “attention to the particular is a way to open into infiniteness.” He does this beautifully in Small Rain, a book of my life.

I was thinking about this on walks with my pup this week. She likes to sniff the tips of twigs. The very tips, specifically. She will touch her nose to the end of twig and sniff it, very carefully. Then she will move on, find another twig, and delicately put her nose to its tiny tip, sniffing. She is so precise about it. It is an incredibly particular kind of attention. She is attuned to something so small, and so beyond my experience. I can’t stop thinking about it.

A Divined Question + A Prompt

One of the biggest joys of my year has been the collaborative creative exchanges I have with friends. This fall, I’ve been working on a collaborative art project. I cannot sing the praises of this practice loudly enough. It is transformative, inspiring, challenging, life-giving, hopeful, silly, and unexpected. I want everyone to experience this kind of artistic freedom and connectivity. I encourage you to try it. Text a friend, ask them if they want to make something with you. You do not have to be a capital-A artist or a capital-P poet to make art with people you care about.

In our ongoing collaborative art project, a friend and I have been using prompts (one thing about me is that I LOVE A PROMPT!) for inspiration. We’re using a process called divining, which is something Leila Chatti came up with when she was working on her latest poetry collection, Wildness Before Something Sublime. She flipped very quickly through books by beloved poets, and then used the words and phrases and misreadings she encountered to make poems. I’ve started coming up with what I call divined questions, which I formulate through various alchemical engagements with beloved poetry collections. My process is a variation of Chatti’s, which is, of course, one of the most beautiful things about art-making practices: they travel, they change, they shapeshift.

In the spirit of creative exchange, I thought I’d share a divined question and a writing prompt with you this week. Here’s the question, divined from Ada Limón: How do we “return and return to this shattering world”?

Here’s the prompt:

Think about a place you love. It can be anywhere—a mountain range, a particular park bench, a room in your grandmother’s house, a river…

Make a list of five ways you would care for this place if it got sick, five things you’d miss about this place if it died, and five gifts you’ve received from this place.

Write a poem in the voice of the place that answers the question: how do we return and return to this shattering world? By “voice of the place” I mean that you are not the speaker of the poem—the place is. Each line should incorporate one image/idea/word from each of your three lists.

If you make something inspired by this prompt, I’d love to hear about it (especially if you make something with a pal)!

We Feed Each Other

The deliberate and ongoing evil of the US government fills me with more rage that I can fit in a sentence. You can find up-to-date information and resources (for if you’ve been impacted by the SNAP freeze/delays and if you want to help support those who have been) from the state of Massachusetts here.

Here are a few additional resources/actions for folks in my little corner of Massachusetts:

The Atlas Farm Store Community Fund: Atlas is probably the dreamiest farm store I’ve ever been inside, and they have started a community fund so that customers who usually use SNAP at the store can continue doing so.

Just Roots: I used to work at this wonderful farm. Many of their CSA members use SNAP to pay for their CSA shares. Just Roots is raising money to cover the cost of these shares through the end of the year, so that members can continue to receive bountiful, beautiful boxes of produce.

Stone Soup Cafe: Stone Soup offers wonderful, pay-what-you-can community meals every Saturday, as well a a free store. They do great work in Greenfield and you can support them here.

As always, a little bit of beauty to send you on your way: It’s been a very good week for the moon.

Thanks for being here, friends. Wishing you all strength and sweetness, as ever.

Reply