- Poetry School

- Posts

- Volume 5, No. 16: Queer Syntax is Infinite

Volume 5, No. 16: Queer Syntax is Infinite

The 6 minutes of television I cannot stop watching

Greetings, poetry people. It’s been a while, and a lot has happened! I wrapped up my semester, which left me in my feelings, because it was my last semester at Greenfield Community College. In January, I will be starting at Smith as an Ada Comstock Scholar! The Ada Comstock program is for non-traditional aged students who want to finish their undergrad degrees, and I could not be more excited to see where this next step of my educational journal takes me. There is absolutely no way I would have gotten here without GCC—these past 1.5 years have been transformational. I have so much gratitude for my professors and classmates. I will definitely be back to visit.

Last Sunday I celebrated the Winter Solstice, the most sacred day of my year, and you probably thought that this newsletter was going to be about that. Or maybe about my favorite books of the year. It is not. It is going to be about the 6 minutes of television I cannot stop watching—the greatest six minutes of queer television I’ve ever seen, let’s be honest. If you have not watched Episode 5 of Heated Rivalry (why?!?) or read the book (why?!?), major spoilers follow.

In the six minutes of television I cannot stop watching, the final six minutes of Episode 5 of Heated Rivalry, a famous hockey player comes out, in a very dramatic way, by kissing his boyfriend on the ice in front of thousands of people after winning the Stanley Cup. The two main characters—closeted queer hockey players in love with each other—watch this happen, separately, on their television screens, and it changes everything for them.

It is not a Coming Out Moment. The scene is not even about coming out. “Coming out” is not even in the room. What happens in this scene—its heartbeat, the thing that makes it come alive, the thing that has made me cry every time I’ve watched it, which I have probably done 35 times—is not public. The trappings—the stadium full of screaming people, the celebrity athlete everyone assumes is straight, the emotional intensity of winning a high-stakes game, cameras everywhere—are just trappings. Set dressing. What is actually going on here is that four queer men are having a conversation. They are speaking to and among each other, both consciously and unconsciously, in a queer language that, to some of us, is decipherable, familiar, known.

This is not a Coming Out Moment.

The thing about the whole concept of coming out is that, for the most part, I hate it. It’s rarely about queer people or queerness. It’s almost never something we do for ourselves. It’s almost always about straight people. It’s something we do in order to move through the world just a little bit more easefuly, to make ourselves more legible or palatable. It gets inside our heads as some kind of pinnacle of expression: to be “out” is to be liberated; to be “closeted” is to be trapped. It’s a false binary, of course, like all binaries. I don’t mean to imply that there aren’t real consequences to being out or not: there are. Sometimes the consequences are literally life or death. But coming out is not innate to queerness. It is innate to to living in a heterosexist world. It is about lack and translation, about what is easily explainable and simply visible. It is not about abundance and creativity and fucking and wholeness and the gloriously messy possibilities of queer embodiment.

When I was sixteen, I had the immense luck and privilege to attend a weeklong writing workshop in Taos, New Mexico. It was not specifically for teens; I was the youngest person there by close to a decade. I met a woman named Lori; we were randomly assigned to the same small writing group and were immediately drawn to each other. She was the first queer adult, outside of my family, that I loved. I’ve been thinking about her a lot these last few months, because I recently learned she died. We’d fallen out of touch long ago, but her friendship remains one of the most important friendships of my life. She saw me. I don’t know how else to explain it. I was sixteen and I had a crush on a boy, who I could not stop writing about, and yet, she saw me. She saw my queerness, my poet’s heart, my longing. She saw the roil in me, and held it. I don’t remember coming out to her or her coming out to me. It was not that kind of friendship. We found each other through a queer language that it remans my life’s honor to speak, to learn, over and over again, to speak. She is one of the people who made me possible.

Last Friday night, I watched two men kiss on my laptop screen, and I watched the faces of two other men, watching them, and I burst into tears, and I could not stop crying, and I skipped back to the beginning of the scene and watched it again, and again, because I understood what was happening as they watched, I saw the language plain on their faces, I felt it in my body, too: that moment of possibility, that miraculous recognition, that bedrock truth which is the opposite of coming out: queerness is what makes queerness possible.

***

I’ve been thinking a lot about queer syntax lately. I’m not sure exactly what it is, and I don’t suppose I’ll ever know—most of the best questions are unanswerable. But I’ve been wrestling with it, and especially with what it means to write with queer syntax, and, more urgently, to live with it. How can I live a life defined by queer grammar?

Earlier this year, I listened to Carl Phillips on Between the Covers (an incredible interview). I will never forget what he said about syntax: "I sometimes think of my sentences as ways of publicly speaking, saying one thing, but those who understand see that, ‘Oh this is a queer person.’ They can see that simply by the sentences—this is a kind of navigation system that refuses to have anyone pin me down."

Carl Phillips is one of my favorite poets; I will spend the rest of my life reading him and tangling with his syntax, which is knotty and tree-like, wild, fraught, complicated, sexy, transformative, transcendent. I don’t know how to translate or explain his sentences and the way they spill across his poems, except to say: I feel their queerness. When he says his sentences are navigation systems that queer people can understand, he is not saying that there is something innately queer about the way he writes (although perhaps there is—I’m reminded of Jericho Brown writing about Claude McKay, and about how all of a queer writer’s life is present in their writing even if they never write about queerness itself). What Phillips is saying is that there is something in his syntax that can be heard, received, and felt by people who are, in mysterious, complicated, and unknowable ways, his kin. His sentences are a queer invitation.

I spent most of the fall writing an essay on Mary Oliver. It’s about a lot of things: how my relationship with her work has changed as I’ve aged, loneliness, being in love, the limitations of language, foxes, death, and, also, queer syntax. Forgive me, but I’m going to quote from my own unpublished work, because what I’m trying to say about the queer syntax of The Six Minutes is connected to this other idea I’ve been wrestling with: how queer language (and thus, queer syntax) is transmitted.

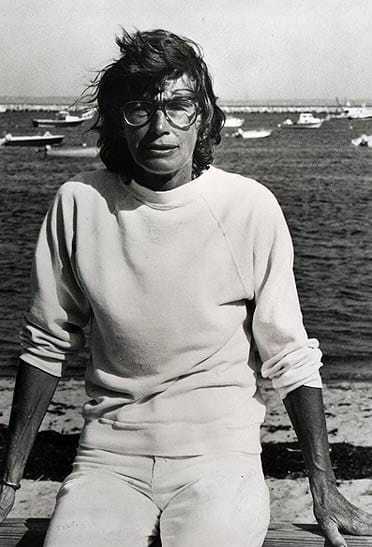

For most of us, queerness is not a language we learn to speak at home. It’s not our first language. Sometimes it is not even our second. It’s a language of possibility, ignited in the dark, passed from person to hawk to oak to person to conch shell to rain to person, on forest trails and tucked inside books with unassuming covers. Its syntax is infinite. Mary used it when she wrote “you do not have to be good,” which means something specific, something bodily and untranslatable if, for instance, you speak a particular queer dialect, if you are a queer woman, or a queer someone connected uneasily but inextricably to womanhood, if you are a dyke, or ever were, even if you’ve found another home now, if you are any beautiful, inimitable embodiment of transness or genderfuckery or femme witchery, and if you have seen the photo, the one in which Mary is not good, the one where she’s braced against a wooden railing by the harbor, the wind in her hair, her face severe and shadowed, the one with the hands, the one with the arms, which, having seen, you will never forget.

I’m working toward a non-definition of queer syntax, and here’s the first part of it: queer syntax is reciprocal. It only activates when there is someone to receive it. A navigational system requires an operator. A star chart, a sextant, a GPS—these things alone can’t get you to where you’re going. You have to actually move your body. Interpret the instructions. Make the turns. Queer syntax exists out in the open, in plain sight, but it only comes alive—it is only possible—when queer people notice it. Carl Phillips’s public sentences with their private queer grammars. Mary Oliver’s queer invitation in ‘Wild Geese’. And this scene, The Six Minutes, which is built with queer syntax. The Six Minutes is a queer navigational system.

Mary Oliver, Provincetown Harbor. A queer invitation.

***

The queer syntax of The Six Minutes begins, quite obviously, when Scott, the hockey player who is about to have a not-coming-out moment, finds himself completely at a loss after achieving his lifelong goal of winning the Stanley Cup. His teammates are celebrating with their families and loved ones on the ice. You can see the moment he realizes that what he just achieved means nothing if he cannot share it with the person he loves. He finds his boyfriend in the crowd, and, once again, you can see the moment he makes a decision. He does not decide to come out. He does not decide to make a statement, a scene, or a grand romantic gesture. The decision he makes is much smaller and quieter. Maybe it’s not even really a decision. When he gestures up into the stands and tells Kip to come down, he’s just living his life. The public spectacle falls away. When the two of them get out onto the ice, when they kiss, the crowd has already vanished. And this is what Shane and Ilya, the show’s protagonists, watching, see. This is the moment in which the queer syntax comes alive, ignites.

Ilya is watching in Boston with his bestie and a bunch of acquaintances. Shane is watching in Ottawa with his parents. Neither of them is alone. Scott and Kip are not alone, either: you can hear the crowd roaring and clapping, and the commentary from the hockey announcers. And yet: there are only four people in this scene. It is not a Coming Out Moment because it is not about straight people. Scott and Kip are speaking only to each other, and, watching, Shane and Ilya—two people who have spent the last 7+ years talking to each other through sex because they do not know how to talk to each other with words—hear something. Queer language is transmitted. A navigational system comes online. You can see it in their faces as it happens in real time. The editing is brilliant. The Coming Out Moment is there, on the surface, all spectacle and polish. It even matters, in the material world we live in. Surfaces do matter. But, beneath it, the moment turned on its head. Beneath it, this other thing. Queerness makes queerness possible.

"Ilya felt like he was watching all the worst things about his life getting sucked up by a tornado.”

There’s a line from the book that is written all over Ilya’s face in the moment when he receives the queer syntax, when it comes alive, when it becomes something that he can use to propel himself forward into his life: "Ilya felt like he was watching all the worst things about his life getting sucked up by a tornado.” In other words: queerness makes queerness possible.

Four queer men having a conversation with and among each other. A conversation that opens a portal: Someone else has done this. “I’m coming to the cottage,” Ilya tells Shane on the phone, which means: I want to try to talk you. Which means: I can’t keep pretending we are alone. The portal isn’t so much about not being the only one, about seeing yourself reflected, about having a role model, about visibility, about the way bravery can spread from one heart to another. These things are not trivial, but they are not what the scene is really about. The scene is about what queer language can do.

Queer syntax is infinite.

Queerness makes queerness possible. I plan to spend the rest of my life discovering all the ways that this happens, but one of them, and I am certain of this, is through the technology of queer syntax. This is why so many queer people absolutely lost our shit when we watched this scene. This is why we cannot stop talking about it. The syntax was transmitted. We felt it in our bodies. We felt our ghosts close. We felt the presence of the people who made us possible, who will make us possible, and of the people we lost before they had a chance to be made possible. In the faces of these queer characters, we read the stars. Something bigger than all of us ignited. It was a private moment, an intimate moment, witnessing this beautifully rendered visual, auditory, and narrative queer syntax, a syntax big enough to hold all the grief, all the joy, all the gifts, all the responsibility, of being a queer human on this planet. I still cannot believe this scene exists.

Queerness makes queerness possible.

Heated Rivalry is a romance. It is a romance adapted right—with incredible seriousness, with a deep and nuanced understanding of the genre, and with more love than I’ve fully been able to process. It shows us—though some of us already knew this—what romance can do. How deep it can go. The Six Minutes is not the be-all-end-all of queer syntax. It is one of its infinite grammars. It reached out to me, and I received it. Like Mary, inviting me into the family of things. Like the poet Gabrielle Calvocaressi saying that “queerness is a portal of connection.” Like Carl Phillips speaking about how his poems knew he was gay before he did: “I sang myself through, or more exactly, one of my selves sang another one through.”

Isn’t this what it is to be alive? Our selves, singing each other through? The selves inside of us and the selves outside of us: trees and my friend Lori who saw me and Mary Oliver walking across the dunes. Two fictional hockey players falling in love and the people who took their story seriously. Grammars of queer joy braided inextricably into grammars of grief.

Here’s what the queer syntax of The Six Minutes ignited in me. Last Saturday, after I’d watched the scene approximately 15 times, I took a walk on my beloved ridge and was flooded, suddenly and completely, with profound gratitude for the gift of queerness. I felt the enormity of the responsibility of the gift. It is not a small or inconsequential gift. It is gift people have been murdered for. I do not take it lightly. I am more honored and more lucky to have received the gift of queerness than I will ever be able to put into words. I watched the sun setting over the hills, and I looked up into the branches of my favorite tree, and I felt the weight of it settling on me: the responsibility of being a queer human on this planet. The responsibility of being a queer human in love, on this planet. The responsibility of being a queer human in love, on this planet, with some small talent for words, for translation, for messy meaning-making, which is to say: connection.

Queer syntax is infinite.

“No, I don’t mind the failures,” Mary Oliver writes, “so long as I am still striving.” All my life, I will keep striving to make of my living a queer syntax that you, whoever you are, can receive and ignite and pass on down the the lineage of hands and words and waters.

Wishing you all sweetness and strength, as ever. If you want to talk about the brilliance of Heated Rivalry, the comments are open.

Reply