- Poetry School

- Posts

- Volume 5, No. 6: Foxes, Pines, Mutual Aid, & Centos

Volume 5, No. 6: Foxes, Pines, Mutual Aid, & Centos

June Reading Reflections

Greetings, book people! I am so excited to be here with you in Poetry School! It’s been a long time since I’ve written an actual newsletter, and I have about 150 things to say, but since I’m planning to ease back into a weekly format, I’m going to keep it short(ish). By shortish I mean that I want to tell you a bit about some of the things I did and saw and felt and read and made in June, but I’m not going to write 3.5 novels.

A quick reminder that if you become a paying subscriber ($5/month), you get access to the Poetry School Syllabus, a guide to 40 poetry collections I love recommended across 10 categories. I think it’s pretty rad—and just in time for the Sealey Challenge!

In June I spent a week in Provincetown during Queer Week at the Fine Arts Work Center. I saw three foxes. I fell in love with Provincetown, hard. I spent some time with my beloved ocean. I swam in my river and my lake. I wrote poems. I missed my book club’s June meeting and felt sad about it (complementary—I love my book club). My community garden plot is growing, slowly. I’m really into viburnum and lupines. As usual, I cried a lot. It rained a lot. I went to my library a lot. The government passed a murder bill. I’m still trying to figure out how to best use my body and words and heart in service of liberation.

In other news, summer classes started this week! I’m taking Drawing Foundations, which is terrifying but super exciting, and an online queer history course, which of course I am also very excited about. I’m sure I’ll have a lot more to tell you about all of this in the next few weeks.

Finally, I have two new poems out! You can read “Impossible Architecture” in the current issue of ballast. “Self Portrait as Bodies in Flux” is out in the new issue of the Tampa Review, which is print only, but you can check it out here.

In this issue...

June Reads

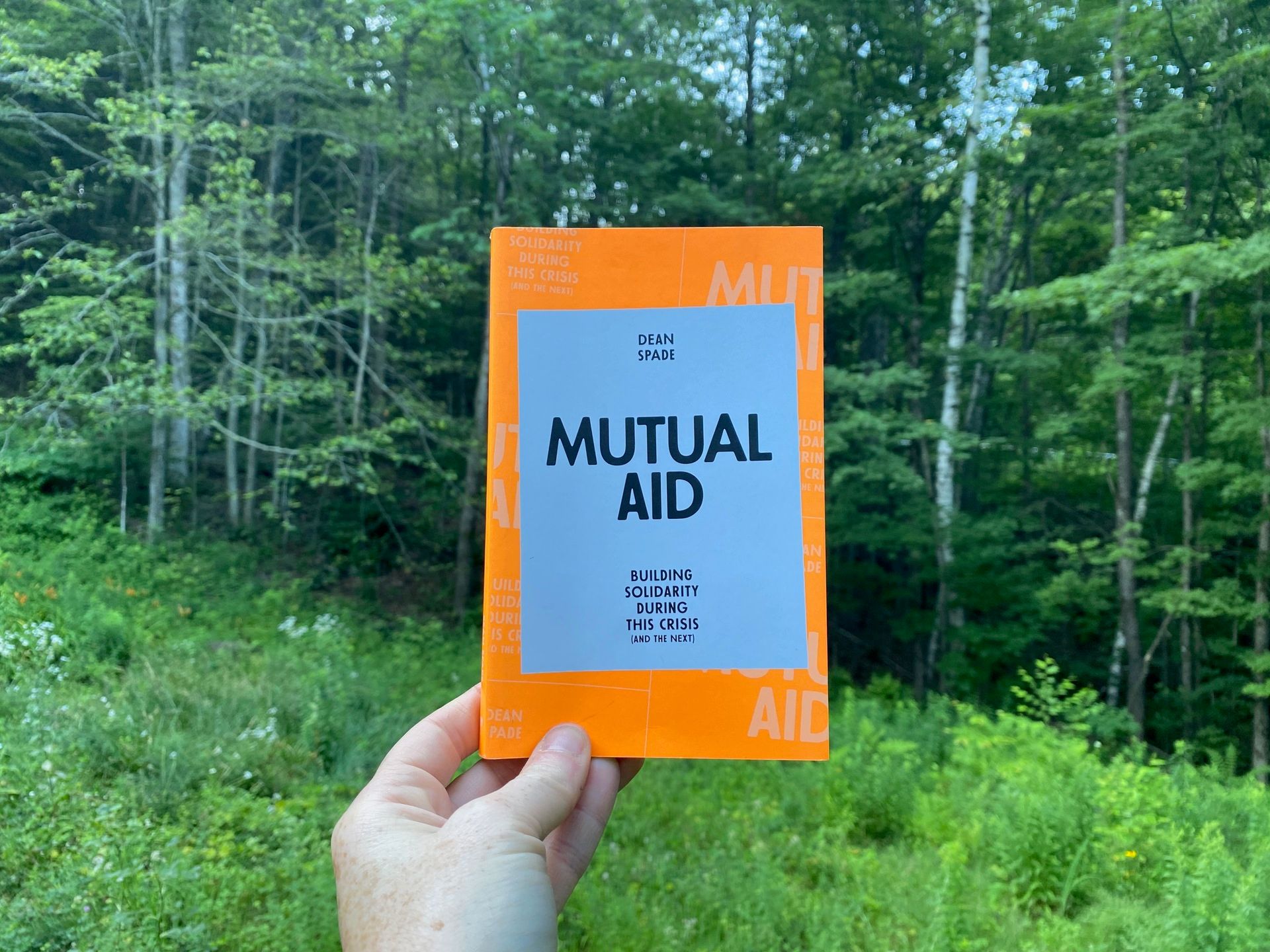

(One) Favorite Read: Mutual Aid by Dean Spade (2020)

This is a fantastic practical introduction to mutual aid: what it is, how it works, why it’s important, and how to do it. It contains exercises, charts, and worksheets—it’s designed to help you start a mutual aid group, get involved in local mutual aid initiatives, and work through common challenges and conflicts that arise in mutual aid groups. Spade defines mutual aid as “collective coordination to meet each other’s needs, usually from an awareness that the systems we have in place are not going to meet them.” He lays out three key components of mutual aid:

Mutual aid projects work to meet immediate survival needs and build understanding around why those needs are not being met.

Mutual aid projects mobilize and build movements.

Mutual aid projects are participatory, based in collective action rather than a “savior” mentality.

None of this is new to me, but I appreciate how clearly Dean lays out the both/and of mutual aid. One of the main points he makes is that mutual aid is not just about fulfilling a need (distributing food, getting trans people access to HRT, etc.)—it is also about understanding the oppressive systems that lead to so many people not having their basic needs met, and working to change those systems.

Sometimes it feels to me like these two things—meeting material needs and working toward a radically different world—are in opposition. Some people are focused on meeting people’s immediate material needs, while others are committed to burning everything down to something new. But we can actually do both of these things at the same time, and Spade has written a concise, practical, accessible manual on how to do so.

What makes mutual aid so compelling to me (and so many other people), is that it is a both/and proposition. It addresses the present and the future. This book made me think a lot about the volunteer and collective work I’m a part of, and how I make the both/and of mutual aid a guiding principle of my life

All the Poetry Collections I Read in June

I read eight poetry collections in June, including one reread (Ocean Vuong), and my monthly Year of Mary book. I can’t pick a favorite but George Oppen was the biggest surprise. Here’s a little bit about each, in the order that I read them.

Diaries of a Terrorist by Christopher Soto (2022)

This collection rages and grieve and wonders: how to be a queer person in this world, how to transform this world, how to love in the midst of ongoing state violence. “We’re tired of writing this poem,” the speaker says in the devastating “All the Dead Boys Look Like Us” and then goes on: “But we wanted to say one last word about Yesterday.” There’s relentless movement, endless questioning: how are we going to get this done? How are we taking care of each other? Tell me who and how you’re loving, what you’re building, the poems say, because we’re dying. I did not love every poem, but I was so moved by Soto’s use of “we” pronouns—every poem is narrated by a “we”. It feels exciting and holy, fraught and hopeful, this insistence of naming the we, of moving outside the boundaries of the self, of making of the self many selves.

Whale Fall by David Baker (2024)

This collection is largely concerned with time and illness—human illness and the illness of the planet, human time and geologic time and the lifetimes of individual creatures and of species. “We live in one time but think in another,” says the speaker in one poem. I kept thinking about weather as I read this—storms and snow and wind, the way the air stirs in a field in the wake of a tractor, the stillness that emerges in the quiet after a bird sings. Baker writes in cycles, of cycles, with cycles—elemental, emotional, violent. Cycles of aging, cycles of death and decay, cycles of glaciation, generational cycles. Many of the poems feel cyclic in form, with lines ending in dashes, or coming back to a repeated image or idea from different vantage points.

Headless John the Baptist Hitchhiking by C.T. Salazar (2022)

This collection kept taking my breath away, line after line. It’s a queer, Southern, religious collection, steeped in rural places—both their physical and mythical realties. There is so much river in this collection, so much water. I kept weeping at the waters that flow through it, from the poem ‘All the Bones at the Bottom of the Rio Grande’ to the retelling/recasting of the flood story in ‘After Us, the Flood.’ All these categories, places, identities, ideas—queer, Southern, religion, rural, story—become unfixed in this collection, flow messily into each other. There’s a restlessness to it, the speaker constantly turning over the stories and lands they inherited, interrogating but also honoring them. It’s dense, but the lines are often sparse, clear, sparkling.

Night Sky with Exit Wounds by Ocean Vuong (2016)

This is an incredible book about lineages of bodies and violence, about desire and art-making and story-making and mothers and the hungry shadows of the Vietnam War. It is brimming and generous and sharp and tender. Perhaps the next time I read it, I will write a review that is more about its layers and artistry. For right now, all I want to write about is the sentences. The lines. Oh my breaking heart, the lines. There is language in this book that makes me believe in language—despite all the hard evidence for the violence language has done and continues to do, despite its cracking and breaking, despite its smallness, despite despite despite—I believe in language because this book exists in the world. That’s what the language joy organ is. It lights up despite.

Bluest Nude by Ama Codjoe (2022)

“I want to be seen clearly or not at all,” the speaker declares in the titular poem of this collection. It’s a stunning line in a stunning book about seeing and being seen. These poems are about the Black female nude—in art, in history, in the imagination. They are about being naked, being made to be naked, about claiming and remaking nakedness. Many of them are ekphrastic. Some are set in museums. They are all concerned with the gaze: who is looking and who is being looked at? Who is being seen and who is invisible? Gazes abound—the gaze of models, the gaze of artists, the white gaze, the male gaze, and, perhaps most beautifully, the gaze that truly sees, the caring gaze, the gaze of Black woman to Black woman through time and space.

Something About Living by Lena Khalaf Tuffaha (2024)

This is a painful, sorrowful, raging, beautiful love letter of a book. It’s a love letter to Palestine and Palestinians, to generations of poets and activists and thinkers and writers and mothers and young people who have used language, and their bodies, to resist occupation, to carve out space for joy, to tell and tell and tell old (and new) stories. In many ways it is a brutal collection, exposing over and over again, plainly, the violence of empire. It is concerned with what language can’t make, or even unmake. And yet, as I believe most of the best political poetry is, it is fueled by love.

The Leaf and the Cloud by Mary Oliver (2000)

I’ve been reading one Mary Oliver collection each month this year, and this one might be my favorite yet. It’s a book-length poem split across seven named sections. I can’t remember the last time a poetry collection made me cry so much. I often cry at poems, but reading this I was full-on sobbing, to the point I had to put the book down because I could not see. It’s a long poem about making—making poems, making a life. It’s about art-making as form, as practice, as revelation, as faith. It’s about faith and mystery and death (always death), and about time and the impossible smallness of this one tiny moment we all get here on this earth, in this world. It’s about love (always love)—loving the world as it breaks, loving the smallest pieces of the world, loving broken. It is full of all of Mary’s usuals: herons, foxes, snakes, roses. It is long, it repeats and circles and spirals, it is answerless, it is questions in different shapes.

Of Being Numerous by George Oppen (1968)

I have not read George Oppen before. I did not even know who he was until I read Small Rain by Garth Greenwell. That incandescent book contains a passage in which the narrator meditates on Oppen’s poem Stranger’s Child. It’s one of the most incredible passages I have ever read in any novel. So obviously I had to read Oppen. I was not prepared for the way this strange, slim book would make me feel. I don’t know how to describe it. It is plain, declarative, at times almost painfully direct. It is also mysterious and strange. It’s a book about living, about days. The long title poem, ‘Of Being Numerous’ is split into 39 sections, and each one pierced me. Lines like: “My daughter, my daughter, what can I say / Of living?” and “It is not easy to speak” thudded through me. But also lines like: “Touched by the dazzle—” This book is difficult, moving, sparsely punctuated. The lines sparkle. There’s a Fanny Howe quote going around, “I would think of poetry as a place where you connect your doubt to the things you don’t doubt. Free-floating doubt wouldn’t trigger the lightning that contradiction does.” I felt that in every line of this collection.

Two Incredible Works of Transfemme Lit

Trans Femme Futures by Nat Raha and Mijke van der Drift (2024)

This is a stunning book—so smart, so juicy, full of so much fascinating scholarship and theory. I read it in a few big chunks and it made my brain explode (complementary). I even bought a copy partway through because I wanted to mark it up and because I know I will be returning to it. It’s one of those books that feels like I will start reading it when I reread it. There’s so much in here I found challenging and inspiring, but the thing I cannot stop thinking about is the way Raha and van der Drift theorize and imagine complicity. I’m used to seeing complicity framed as a negative thing, as the opposite of generative, as something we’re stuck with, rather than something that can lead somewhere else, a symptom of our failure rather than of our entanglement.

Debarati Sanyal explains complicity as being folded into a situation - not standing on the sidelines (perhaps looking at the guilty one who transgressed the rules, perhaps shaming them), but rather a call to action and shared responsibility for a situation (and how it might be changed).39 This combines with the attentiveness at the heart of our transfeminism - highlighting forms of care that not only attend to needs, reproduction, or survival, but also to a reality to ensure it is not curbed by discursive categories.4 Such attentiveness is saturated with the possibilities of exchange that occur in close proximity. Thinking about complicity helps us, on the one hand, to see positionality as a marker that determines the demands of hegemonic structures on our lives, and on the other hand, indicates how our becoming and our politics shape our understandings, relations, relatability, and attention.

Any Other City by Hazel Jane Plante (2023)

I reread this for the Queer Your Year book club and, if possible, I loved it even more the second time around. It’s a fictional memoir told in two parts, set in the same city. What I loved most on the reread is the openness—a kind of radical welcome—that gets the main character, Tracy, through two hard moments in her life. In the first half of the book Tracy is t20 and alone in a new city. She hasn’t come out to herself as trans, and whatever she knows of her gender and her womanhood is mostly subconscious, or, at least, she’s not articulating it to herself. And yet she falls in with this group of trans women artists, including two musicians who invite her into their home and lives and hearts, and who do so without reservation or qualification. She’s presents and talks about herself as a cis man. These trans women don’t question her gender, they don’t tell her she’s a trans girl, they don’t really even ask her to talk about it. Sometimes she’s super awkward or says something transphobic without meaning to, and her friends don’t let her off the hook, exactly, but they don’t kick her out of their lives, either. I cried my way through this section, through the space these trans women make for this character who doesn’t know herself but needs, desperately, somewhere to simply be, as she is, right then.

This pattern of radical welcome, of queers holding space for each other, happens again in the second half of the book. Tracy, now in her 40s and a famous trans musican, is back in the same city after from a traumatic breakup. She meets a variety of queer and trans folks with whom she has sex, makes music, talks. It’s totally different from the first half of the book but it feels the same way: a feeling I can’t quite put into words—sad, hopeful, present. I adore this book with my whole heart.

A Poem & Its Worlds: Provincetown

At the end of June, I got to spend a week in Provincetown at the Fine Arts Work Center during Queer Week. I got a scholarship to take a poetry workshop with Cameron Awkward-Rich. The entire week was a poem—a book of poems, a universe of poems. I’m still processing everything I thought and felt and made and cried about. Here are 10 moments/reflections from the week.

1) My friend Mary, who grew up in Provincetown, told me that it’s “spirals upon spirals” when I told her that I could not wrap my head around the geography. I watched the sun rise and set from the same beach, over the same ocean. Spirals upon spirals: time, ocean, light, poetry.

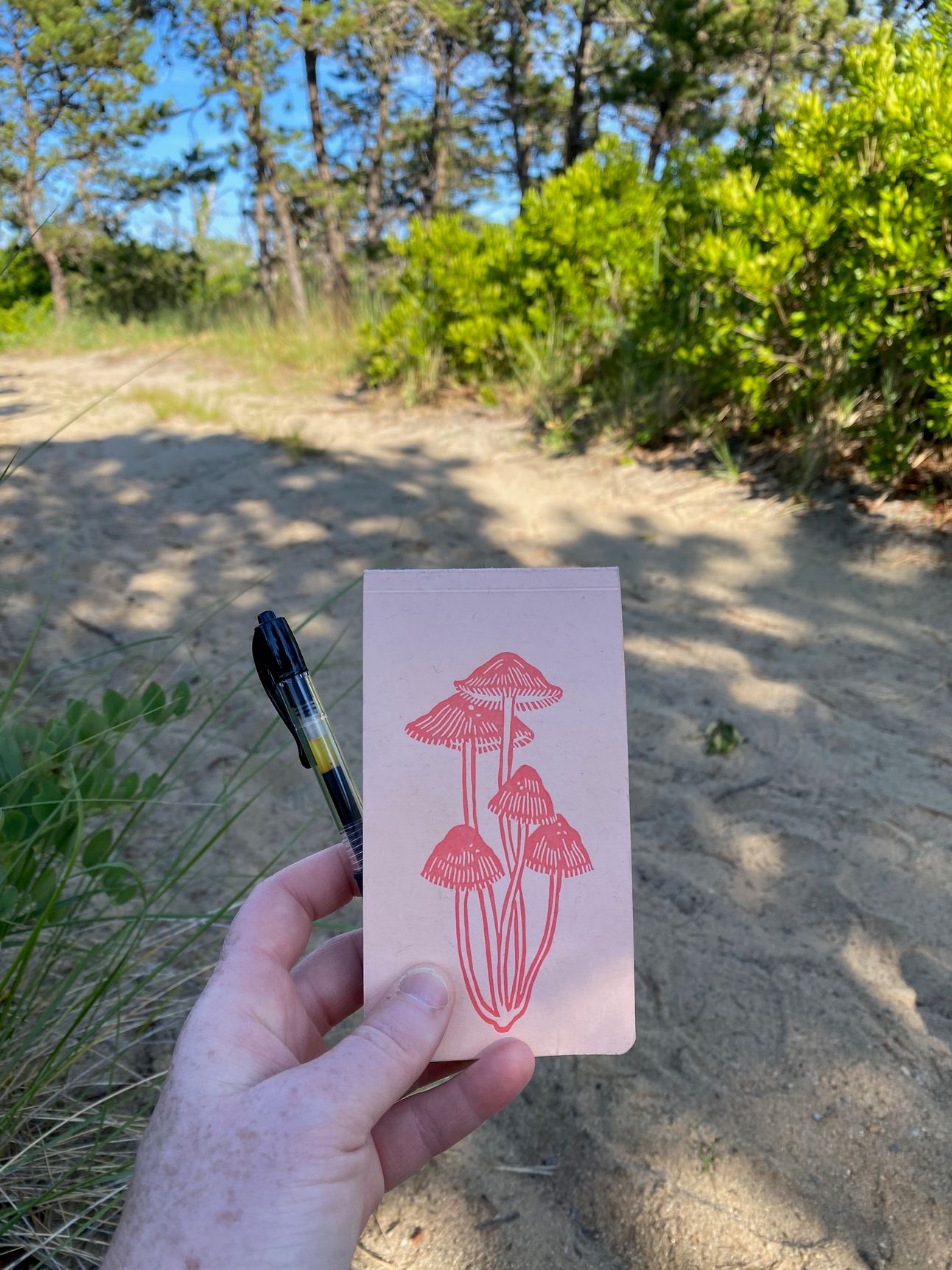

2) I spent a lot of time walking around writing poems in this mushroom notebook sent to me by a dear friend and poetry penpal. I walked on paths and through woods and around ponds that Mary Oliver walked. I texted my friend from Provincetown about how hard I was falling for this wild, beautiful place. I talked to my pup. I carried around so many people with me, even though I spent much of the week alone.

3) I fell in love with the dunes. I had no idea what it would feel like to be out there in that wild, windswept place. The landscape is familiar to me—the pitch pines and rosa rugosa, the scent of bayberry, the sand—but the dunes are unlike any other place I’ve ever been. Walking among them it is almost impossible to believe that, a few miles away, there’s a bustling town. I am dreaming of returning.

4) Almost every night I drove to Race Point Beach and swam as the sun set. The water was deliciously cold.

5) Everywhere I went, Mary was there. I thought about her walking down Commercial Street, as I passed some of the houses she lived in. I thought about her whenever I smelled roses. I thought about her in the early mornings in the dunes. I felt her presence on my skin like water. I sensed her in the light, the colors, the pitch pines, the ponds.

6) Each night at FAWC there was a faculty reading. I cried through all of them. Cameron Awkward-Rich read from his upcoming book An Optimism (which you should preorder). He also said something I have not been able to stop thinking about. During the Q&A, someone asked a question that gets asked a lot at readings these days: what’s giving you hope? He replied that the future isn’t determined yet, that he’s trying to do “the opposite of remembering.” It’s not that remembering isn’t important, but that making also matters, being present, being open to surprise.

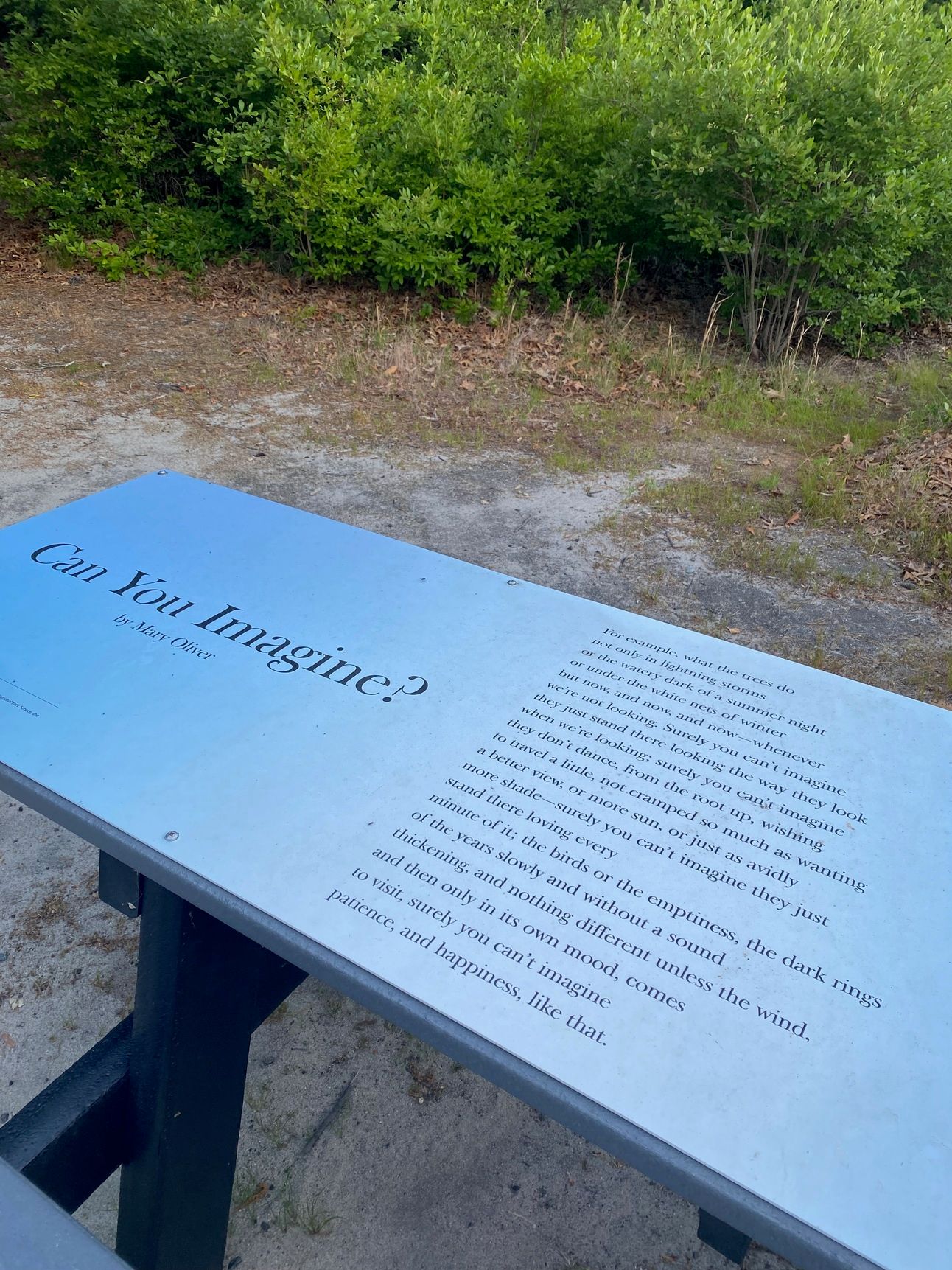

7) In one of the essays in her book Upstream, Mary Oliver wrote that “the center of my landscape is a place called Beech Forest.” Beech Forest surrounds Blackwater Pond, a place that appears again and again in her poems. I walked around the pond in the early morning, alone with the herons, the frogs, the sunrise, my pup. I sat on a bench overlooking the pond and read her poem “Can You Imagine?” I was not prepared for the impact this pilgrimage to one of the most sacred places of one of my most sacred poets would have on me. I feel forever changed.

8) I was at a poetry workshop! I didn’t just spend the whole week walking and communing with Mary Oliver! The workshop itself was amazing. We talked about repetition, about the poems that come from a repeated practice, and about return—what does it mean to return to a poem, an image, a moment, again and again? I wrote a lot that I’m still slowly untangling.

9) In addition to the amazing writers who read (Alexander Chee! Andrea Lawlor! Carmen Maria Machado!) there were several visual artists who gave incredible presentations. I was so moved by Miriam Klein Stahl’s presentation on printmaking and activism. I got to hear Catherine Opie give a talk! My favorite part was how she talked about taking portraits of mountains. She said that she thinks mountains are just out there living, and they get roped into being masculine, into carrying all these toxic traits we put on them. So she decided to take portraits of mountains as a dyke.

10) On my first night in Provincetown, driving through the dunes at sunset, I saw a fox trotting along the side of the road. I felt a wind move through my body: the ghost of Mary Oliver, or maybe just the universe saying: pay attention. I saw three more foxes during the week, including one carrying a dead squirrel in its mouth. I wrote a lot of poems about the foxes.

Tree Talk

I’m in love with this tree than leans over my spot on the Green River. I’ve known this particular tree for about five years now, and I love watching it change from early spring to late fall as I swim beneath its branches.

Visiting the island where I used to live a few weeks ago, I spotted this new-to-me tree, the Japanese black pine. I used to live on Nantucket, and I was walking one of my favorite walks when I saw it. Nantucket (along with the Cape, and a few other locations in New England and New York), is home to sandplain grasslands, a unique coastal environment of grasses and small herbaceous plants that thrive in sandy soil. Though sandplain grasslands used to cover large swaths of New England, they are quite rare today. Japanese black pines were introduced to Massachusetts sometime in the early 1900s, and, after falling in love with this tree (look at it!), I learned that they threaten sandplain grassland biodiversity by encroaching and shading out grasses and other species.

I try to avoid language like “native” and “non-native” when it comes to plants, because ecosystems and landscapes are complicated, relational, and constantly changing. Some plants settle easily into new ecosystems; others wreck havoc. People, oceans, and landmasses move (or are moved by force or violence). I think this is a stunning tree. I understand the impact it’s having on a fragile ecosystem I love and, still, look at its needles, its cones, the shape of its branches.

I don’t have a point or a conclusion. I’ve just been thinking about living with contradiction, and making space to hold many truths, ideas, and feelings at once.

Citation Station: “Golden Centos”

In the welcome email you all received, I included a poll asking what you’re most excited to see in this new iteration of this newsletter (and if you didn’t respond, you still can, just go find the Welcome to Poetry School email). A lot of you expressed interest in hearing more about my own creative process. So I thought I’d share a little bit about some of the poems I’ve been working on this spring—which, surprising no one, are deeply citational.

At the end of May I got the idea to write a poem in response to every poetry collection I read. I love responding to poems this way—often my favorite collections make me want to start writing immediately. Sometimes, it feels like they require it of me. I always mark up collections as I read them, underling or flagging lines I love. What better way to write a poem-response to a collection than with actual words from that collection?

I don’t really know where the idea for a “golden cento” came from. Here’s how it works: after I finish a collection, I type up all the lines I’ve underlined that I love (my “heart lines” as Tiana Clark calls them). Then I make a little cento (no more than four lines). A cento is a poem made up of the work of other poets. Then, I use each line of the cento to write a golden shovel—one line per stanza. A golden shovel is a form invented by Terrance Hayes, where the end words of each line in the poem form a borrowed line from another poet (originally Gwendolyn Brooks), so that, if you read the last words of each line vertically, you read the borrowed line (like this). It’s a form I adore and use often.

I call these “golden centos” because each stanza is a golden shovel, and, read vertically, the lines formed by the end-words make a hidden cento. I could write a whole essay about the wonders of this form. So far I’ve written golden centos after Carlina Duan’s Alien Miss, Tiana Clark’s Scorched Earth, Mary Oliver’s White Pine, and Jenny Geroge’s After Image. Everything I write is a conversation; this form makes the conversation visible.

Good Words

These portraits are stunning.

I loved this piece by Hanif Abdurraqib. Here are some snippets of it if you can’t get past the paywall.

The poet Andrea Gibson died this week. Their work is an earnest love song to the world, to aliveness, to grief. Here is a poem of theirs I cherish.

A Question

I’m busy getting ready for The Sealey Challenge, which is always one of my favorite events of the year. 2025 will be my 5th Sealey! In August, along with poetry lovers all over the world, I’ll read a poetry collection every day. August is one of my least favorite months of the year, and the Sealey always helps me get through it.

Obviously I’ll be writing about the Sealey here (and on IG). I have some ideas about how I’d like to reflect on and share the experience, but I’d love to hear from you. Vote in the poll below and let me know what you’re most excited about. Also note you can add comments to the poll, so if you have other ideas, let me know!

Wonder & Care

Patty Berne, disability justice activist, artist, and co-founder of the performance group Sins Invalid died this past May. Perhaps you’ll join me in making a donation to Sins Invalid in her honor.

As always, a little bit of beauty to send you on your way: my love looking silly and perfect in front of my love, the Atlantic Ocean.

That’s it for this week! Please come talk to me in the comments about what you’ve been reading, what amazing trees you’ve seen recently, what your Sealey plans are, what’s getting you out of bed. Come tell me your favorite Andrea Gibson poem.

Reply