- Poetry School

- Posts

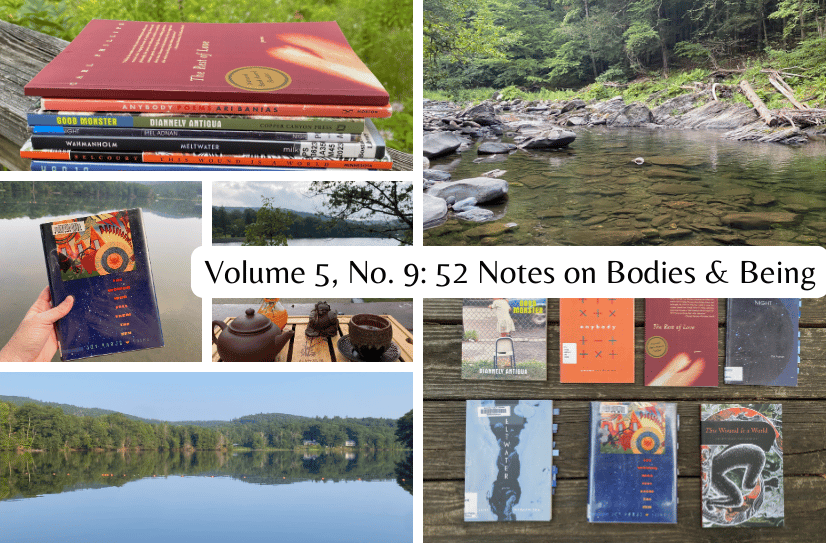

- Volume 5, No. 9: 52 Notes on Bodies & Being

Volume 5, No. 9: 52 Notes on Bodies & Being

reflections on the first week of the Sealey Challenge

Hi, poetry people! I’m sending this newsletter on Friday instead of Wednesday because I wanted to write about the first week of the Sealey Challenge, which started last Friday. I’m also trying to be looser about expectations and structures. There’s no rule that says I have to send newsletters on Wednesdays.

Thank you to everyone who has donated to the Sameer Project through the Open Books Sealey Challenge fundraiser! We raised $225 in the first week. I’d love to get to $500 by the end of the month. You can pledge here or donate here.

Last week my friend Charlott sent out her wonderful monthly newsletter (which you should subscribe to if you haven’t already). In a series of numbered notes, she wrote all about her recent trip to Paris and London. I absolutely loved reading the newsletter, not just because of all the books and art and ideas and observations she shared, but because I find this particular form so exciting. So I’m copying her today with notes on the first week of this year’s Sealey.

On Friday, the first day of the Sealey, I bring my tea things to my beloved lake, and, after my swim, set up at one of the picnic tables overlooking the water. I love this ritual: the tea, the view, my book. About ten minutes after I start reading, the landscaping crew arrives to tend to the park where the picnic tables are. Suddenly, all around me, the sound of mowers and weed whackers. I sit for a few more minutes—one more pour—and leave. It’s too loud. I think about mornings and rituals. I think about the life I used to lead on Nantucket, when I worked as landscaper. On the island, this was a deeply gendered job. I worked as a gardener on an all-women crew. We planted and pruned, weeded and mulched. We did not operate machinery. The all-male crews (who worked for different companies) did that. They mowed, weed-whacked, and pruned privet hedges with their electric pruners. I think about silence. Who lives inside it. Who lives outside of it.

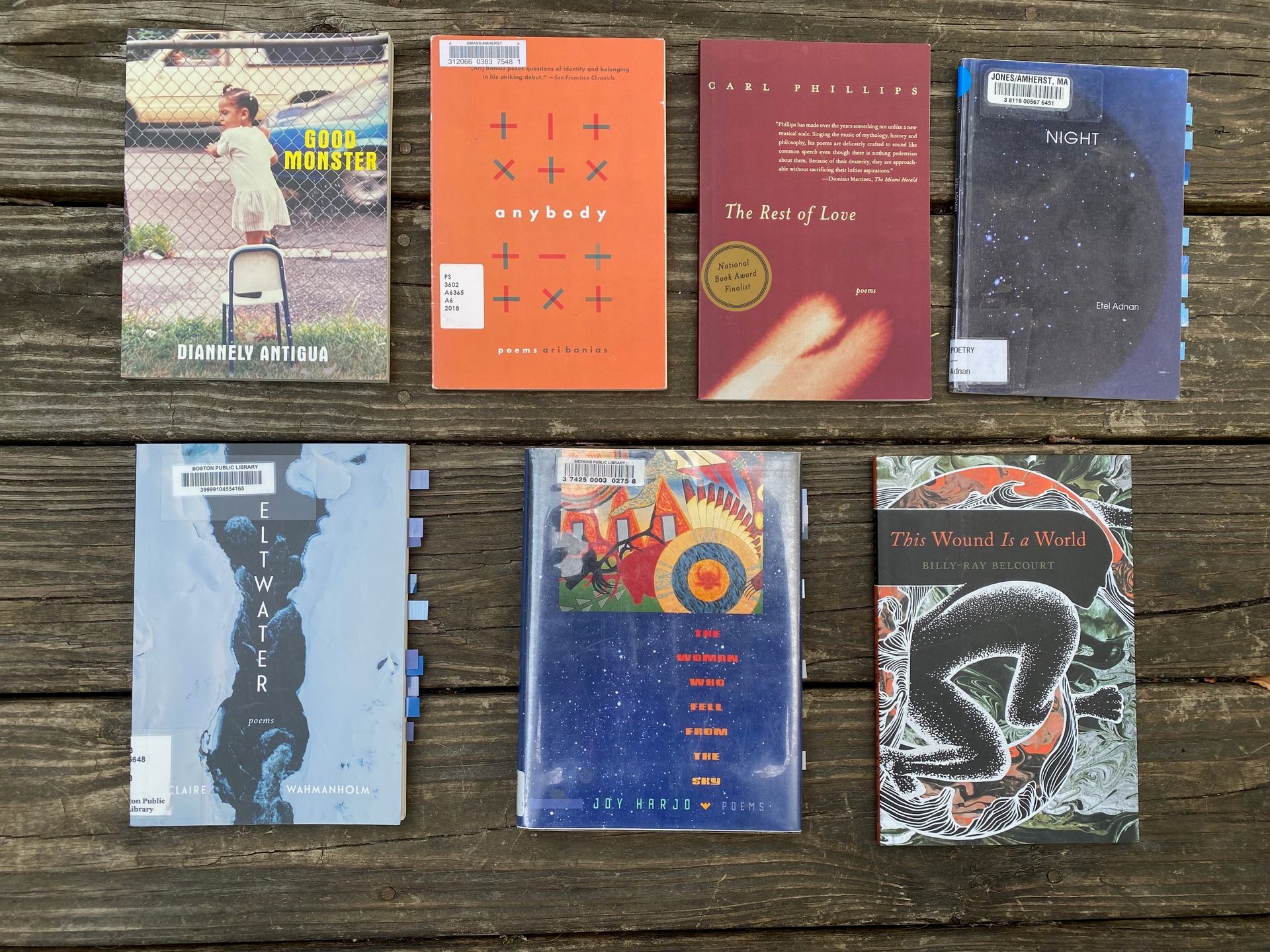

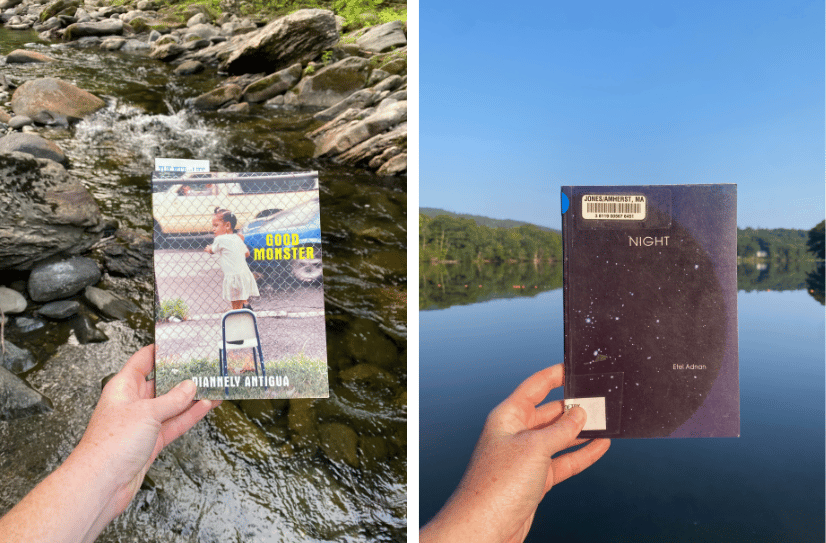

Earlier this year I wrote a long poem in the form of a notes section. The poem itself was notes on poems that do not actually exist. They only exist as ghosts in the poem. The notes section in Good Monster contains a QR code to a playlist for the book—each poem gets its own song. I’ve been thinking about note as form for months now, ever since reading Christina Sharpe’s Ordinary Notes. The notes in This Wound is a World lead me to Ocean Vuong, Jennifer Espinoza, Bhanu Kapil, ALOK. I’ve come to realize that voice notes are my favorite method of communication. I love all the contradictions they hold, the portals they open. What is it about notes? In the notes to The Rest of Love, Carl Phillips mentions a sermon preached by John Donne in April/June 1623. The specificity of this moved me to tears.

On Tuesday, in the hot afternoon, I’m walking with my pup Nessa in the woods by my house and she lies down. She easies her old body onto her side and just lies there on the fallen leaves. I think about the knowledge she holds in her body. I think about the world she lives in, and the world I live in, and the places they touch. I stand there next to her, waiting. Eventually, she gets up. We keep walking.

There is a family of geese at the lake. I’ve been watching them since April. There are also two bald eagles who live there. On Sunday, I watch one of the eagles cut across the sky. A few minutes later, a great blue heron flies in a rush of wings up from the water and lands in a tree just above where I am sitting, reading Night by Etel Adnan.

Billy-Ray Belcourt: “if i know anything, it is that “here” is a trick of the light, that it is a way of schematizing time and space that is not the only one available to some of us. maybe i am not here in the objectivist sense. maybe i am here in the way that a memory is here.” (From “If I Have a Body, Let it Be a Book of Sad Poems” in This Wound is a World.)

I’ve been writing poems in the form of voice notes. I’ve only finished one: “Voice Note to Orion’s Belt After Thirteen Years of Silence.” Who do you long to leave a voice note for in the form of a poem?

On Instagram, Nicole Sealey (for whom the Sealey Challenge is named), posts a line from the poem “Snake in the Grass” in Gail Mazur’s collection The Common: "Can’t you relent, can’t you love yet / your small bewildering part of the world?”

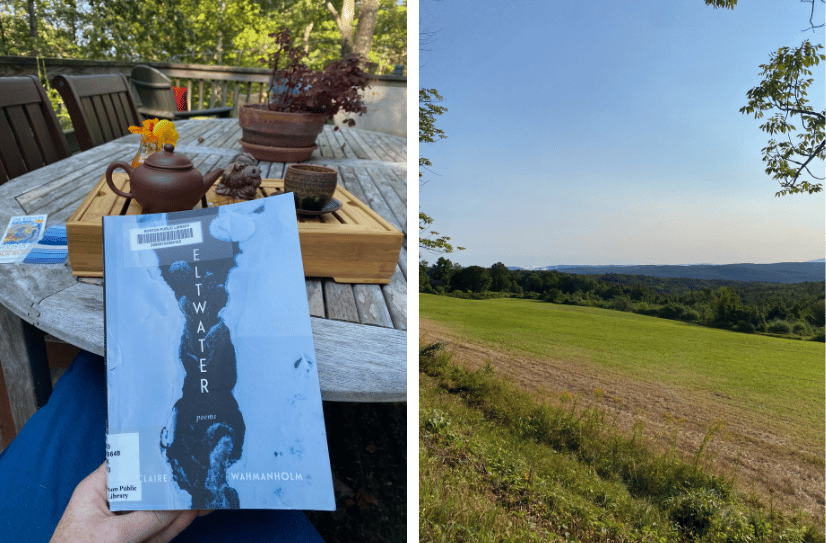

On Saturday morning, on my porch in the early morning sun, I read Meltwater by Claire Wahmanholm, Nessa lying next to me on the smooth, old wood. Light in the oak tree above me. The bitterness of tea, poured and poured again. Clouds, a cardinal, pots of basil and mint. I read in the sun and feel my body on the earth, fragile, wild, here. I kept putting the book down to cry. Eventually I put the whole book aside, to tend to the edges of my heart, its sore and softening places.

There are a series of incredible prose poems in the collection titled with letters: “O", “M”, “P”. Each full of words that hold those letters. They are cisterns of cascading sound, heavy with loss, wild with love. I am so moved, so changed by this whole collection that I spend most of Saturday afternoon writing a poem in this style, after Wahmanholm. I write it for a friend and send it to her. All day, I feel my heart.

Another friend is rereading Ordinary Notes this week. She sends me photos of pages she loves, little windows into her experience of the book. Her texts become their own kind of note. I think about how notes are often passed. How notes are sung. One of my favorite lines from Alexander Chee’s novel Edinburgh: “I had wanted to take something inside myself, like I had once drawn a breath, and then to send it out, as I had sung. To say that you make something out of thin air: you can, if you sing. You can make an enormous number of things this way.”

We meet virtually for the Queer Your Year book club to discuss This Wound is a World. We talk about the title—what it means and what it feels like. Someone brings up something I cannot stop thinking about, the “ecosystem of a wound.” Wounds are, indeed, worlds, teeming with life, full of bacteria, always changing. Our lives are made up of endless transitions. World to world. Wound to wound.

On Saturday night my friend Kristin and I go to see a circus performance. It’s a collection of seven long-form circus acts circling around the theme of unruly bodies. It’s incredible and moving, though I’m also thinking about what kinds of unruly bodies are missing from the show (fat bodies, visibly disabled bodies), and why. There are aerial acts of all kinds (straps, fabric, hoops), a tightrope act, dancers. All night, I watch the performers and their shadows. The lighting creates two or three shadows of each performer—the person spinning through the air and their shadows spinning alongside them. I think about how these acts are really duets, quartets. It’s incredible to witness these moments of spontaneous co-creation between shadows and bodies. This, too, is how it feels to create poems. There is the me making the poem and the me who is the shadow, who lives inside the poem.

Claire Wahmanholm: “Therefore be deep-dwelling muscle. Be sweet vegetable / a moment longer. Before us lies a fatal, blossoming desert, full / of heat and shadow. I am about to set my heart down / into a wild burrow. A clock is about to start.” (From “You Will Soon Enter a Land Where Everything Will Try to Kill You” in Meltwater.)

At the Pocumtuck Homelands Festival, I buy a pair of beaded quill earrings. I spend a while talking to the artist. She tells me about finding the quills, how she came across a dead porcupine one morning while hiking in the woods, how the quills were especially thick and beautiful, perfect for beading, the kind that’s often hard to find.

Notes as tiny winged vehicles of transformation. As love sent back and forth in ink and electrical signals, associations and dreams. Notes as a mechanism of change. Notes as a small language, a language between. Joy Harjo: “We are a small earth. It’s no / simple thing.” (From “Promise of Blue Horses” in The Woman Who Fell From the Sky.)

On Monday I pack up my tea things and my book and go to the lake in the early morning. But it’s too smoky to sit outside for any length of time. I take a short swim and leave. All week, the smoke sits in the sky, turning the hills dull, hazing the horizon. I check NOAA for air quality alerts. Claire Wahmanholm, from ”O”: “O Earth, outgunned and outmanned. O who has made orphans of our hands.”

Earlier this year, my mom found a diary my grandfather kept in the summer of 1936, just before he turned 16. She’s been reading and transcribing it, and each day, she sends out the corresponding entry to the whole family. Currently he and a friend are on an epic-sounding bike trip through Vermont, about 400 miles round trip from Medford, MA, where he lived. On August 4th they stayed at a hostel in Brattleboro, which was apparently less than perfect. From his diary: “A swim in the river however, made us feel much better and at the same time washed off an inch thick layer of dirt.” My brother did some research into the American Youth Hostel they likely stayed at, and concluded that they were swimming in the West River—a place I also love to swim.

Diannely Antigua, from “Diary Entry #5: Self Portrait as Revelations”: “Permanence is beastly.”

There’s a series of poems running through Meltwater, all titled “Meltwater,” all erasures of “How to Mourn a Glacier” by Lacy M. Johnson. Wahmanholm only used each word in the source text once, so with each erasure, the word pool shrank. These poems erupt as sobs inside me, flow out as something else. I’m still trying to figure out how to write about them.

Billy-Ray Belcourt, from “Something Like Love”: “there are days when being in life feels like consenting to the cruelties that hold up the world.”

But, also, Joy Harjo: “I’m not afraid of love / or its consequence of light. (From “The Creation Story” in The Woman Who Fell From the Sky.)

My friend Kristin, responding to my review of Meltwater, a collection we both adore (and that she recommended to me originally) says, “it reminded me that the meltwater refers to the glaciers melting but also the melting of pain, released as tears.” For the rest of the day, I think about this. What grows, watered by grief. So much loss is final, ugly, banal, manufactured by empire, imperialism, capitalism. And, alongside: “remember: grief is a way of making claim to the world.” (Billy-Ray Belcourt, from “God Must Be An Indian” in This Wound is a World.)

"Can’t you relent, can’t you love yet / your small bewildering part of the world?”

I read Joy Harjo’s collection The Woman Who Fell From the Sky with my friend Surabhi. I text her that it reminds me a bit of 19 Varieties of Gazelle by Naomi Shihab Nye, another book we read together. The way both of these poets overflow their storytelling with love—for their people, for their people’s stories—feels similar. She responds that they are both very grounded poets.

Notes against numbness. Notes as notices of affection. Navigational nourishment. Into these narrows, I cast my torn net of punctuation. Listen. Acorns, nectar, northern cardinals, a universe of neighbor nebulas. Notes named and nameless. To send a note is not to abandon what’s broken, but to sing its brokenness plain. Extinction’s on the horizon, in the distance, is sitting down to dinner. Soon it will want the noodles and the nutmeg. It’s coming for nettles and nasturtium. Make a note a question. I’m singing too: notes against nationhood, notes unnarrated, notes to nurture whatever happens next. Our planet of mineral and wind. The moan of a note newborn, so mournful, unbroken in the morning. When a note begins with wonderment, even its ending is infinite openness.

Grounded. Earth-bound. Bound as in “we are each other’s harvest, we are each other’s business.” Billy-Ray Belcourt: “i made a poem out of dirt and ate it." (From “Towards a Theory of Decolonization”.)

Etel Adnan: “Lines of trees lining a dry land form a line of pilgrimage. There’s a beyond-ness to words.” (From Night.)

In The Woman Who Fell From the Sky, every poem has an “afterward,” where Harjo shares inspiration and process notes. She expands upon the poems, asks herself questions about them, honors the people and places she has co-created with. I’ve often heard something along the lines of “the work should stand on its own” in various literary circles. As in: if a writer wants and/or needs to expand on their work, to say something about it, to “explain” it, it’s not successful. What rubbish. Poems aren’t written or read in isolation. Making is a messy web of relation. There’s no such thing as a book that “stands on its own.” That’s another myth, like the myths of individualism and solitary genus, rooted in white supremacy and capitalism. Making the making visible is beautiful.

The title of a poem in Meltwater: “At the End We Turn Into Trees”. Let it be so. Let it be so.

On Wednesday morning I go to the river, set up my tea things on a flat rock at the edge of the rushing water. Whenever I have tea out in the wild world, I bring a tiny vase, and into it I put something I collect from wherever I am. A flower, a branch, some greenery. This morning, a few stems of purple Joy-Pye weed, already fading. I learned this from the friend who introduced tea rituals into my life. Before I leave, I give the flowers to the river.

At the river, I’m reading a new-to-me Carl Phillips collection, The Rest of Love. Every few minutes I look up and watch the water moving, tumbling down its course of rocks. A river is never still, not even when it appears to be, but rivers invite me into stillness. This is also how Carl Phillips’s syntax makes me feel. It is knotty and full of movement, always going somewhere, words and clauses stacked in loops and swirls. And yet, it invites me into slowness and stillness. From “The Rescue”: “first a river // then the ceaseless muscle-work / of a history bright / and dark”.

Etel Adnan: “Water brings energy the way memory creates identity.”

I have a community garden plot where I only grow flowers: zinnias, snapdragons, rudbeckia, strawflowers. I love filling my house with them all summer. But I haven’t been to the garden in several weeks. It has been hot. It has been smoky. I have been so busy. I’ve been stressed about this. What’s the point of having a garden if I can’t even be bothered to visit it? But then I think about all those flowers out there under the sky: the frilly red and orange marigolds, the pale yellow zinnias, the bright purple ageratum. I think: let the bees and butterflies have them. Claire Wahmanholm: “I could have just loved / the earth instead of inventing new ways to hurt.” With my blessing, let the tiger swallowtails and painted ladies have them.

Surabhi and I read The Rest of Love together. We both love Carl Phillips (CP in our text thread) and we’ve read him together before. We talk, as always, about his syntax. I realize that now we have our own syntax to describe his syntax. What I mean is that, while we always find new things in his work, we also always return. We loop. I cherish our ongoing conversation.

I ask my friend and poetry penpal to choose some books for me to read during the Sealey from my library TBR. She asks if she can send her recommendations by postcard (a thousand hearts, yes). The postcards (two) arrive a few days before the Sealey starts. One of the books she recommends is Meltwater. “I haven’t given back the copy I’ve been reading to the library yet,” she says. Now I understand why. I don’t want to give mine back either.

Recently I’ve been haunted by names, the act of naming. I want to name everything. I want to reject names and their boundaries. So much power in naming, unnaming. Reverence, violence. In “The Naming,” Joy Harjo writes, “I think of names that have profoundly changed the direction of disaster.” I think about how, when I enter the water—the river, the lake—I say, out loud, “hello, beloved.” The Green River. Ashfield Lake. Do these beings have their own names, unknown to me? They must. Carl Phillips, in “Pleasure”: “Not memory; / not the naming—which, if a form of / remembering, is also // a form of to own, possession, / whose lineage / shifts never: traced // far enough, past hope, back across / belief, it ends always / at desire—”. Memory, possession, hope, belief, desire. I trace names through this week’s words. Erase and trace and trace again.

On Thursday morning I go to my favorite bakery before class. I order a bagel and a tea and read the first few poems in Ari Banias’s collection Anybody. It reveals itself to me immediately as a collection interested in the fractures and weavings in “we.” I read the last few lines of the first poem “Some Kind of We” over and over: “and I / am trying to write, generally and specifically, / through what I see and what I know, / about my life (about our lives?), / if in all this there can still be—tarnished, / problematic, and certainly uneven—a we.” I look around the cafe, think about the we, gathered and ungathered. Someone from my drawing class comes in; we chat. My hair is still damp from my morning swim. The air quality is better today, not perfect. “I am sure now / there is no true body,” says Banias.

This Saturday is the monthly Great Falls Books Through Bars volunteer day, where we’ll be responding to letters and sending books to incarcerated folks. Before each volunteer day, members of the collective take home some of the letters we’ll be responding to to check them before the event. This process involves looking up the letter-writer in the state or federal system to verify their information. Sometimes people get moved between facilities, and we want to make sure the books reach them. I spent some time checking letters on Thursday night. Every now and then, a moment of sweetness: I learn that someone has been released. But more often, I have the bewildering experience of reading a letter from a human being—maybe someone who’s trying to learn Spanish or is really into monster romance or is eager for nonfiction on queer history, someone with distinct handwriting and a particular tone, someone who makes jokes or sends gratitude or mentions that they love drawing animals—and then typing their name into a database and learning how many more years they will be locked up for. Is there a way to end this note? This world breaks me. Billy-Ray Belcourt: “what happens when wounds start to work like bandages?” Maybe I’ll see you on Saturday.

Joy Harjo: “If I am a poet who is charged with speaking the truth (and I believe the word poet is synonymous with truth-teller), what do I have to say about all of this?” (From the afterward to “A Postcolonial Tale”.)

Several of my friends who are doing the Sealey Challenge are also, like me, participating in the Open Books fundraiser for the Sameer Project. On Thursday I donate in their names—$5 here, $5 there, $10 over here. I’m also donating in my own name. This is just a way of saying: We all contribute. We help each other. We do what we can. Sometimes we do big things. Mostly, we do small things. We do care, little by little.

The animating question: “if in all this there can still be—tarnished, / problematic, and certainly uneven—a we.”

Carl Phillips, from “Singing”: “Hazel trees; / ghost-moths in the hazel branches. / Why not stay?”

A tiny selection of gifts I received this week, in voice notes from friends: A description of a magical garden party. A moment of ease in the body, recounted. A new-to-me album, accompanied by a tangle of thoughts on translation. A book review and recommendation. A story about a beautiful moment/ritual at a funeral, full of love.

The very first sentence in the preface to This Wound of a World is: “Poetry is creaturely.” Belcourt goes on: “the lyric "I" opens up on itself as well as particularizes; the poem brings us into our bodies and thus readies us for the touch and affection of others.” The poems that follow body and unibody. Belcourt uses “body” and “world” as verbs. (The last line in the last poem in Anybody: “Time to world.”) What does it mean to unbody? How do we dissolve into the world, into love, into each other? Can we? Isn’t the “I” in poems a way of doing this, or attempting to? In one poem, Belcourt says: “if i have a body, let it be a book of sad poems. i mean it. indigeneity troubles the idea of "having" a body, so if i am somehow, miraculously, bodied then my skin is a collage of meditations on love and shattered selves.” All week I think about the violences and possibilities of unbodying. Ross Gay, always speaking in my ear: “We are profoundly made of each other.”

“Can’t you relent, can’t you love yet / your small bewildering part of the world?”

Ari Banias, from “The Feeling”: “That we imagine we cannot feel the wars / is an American feeling. That we cannot see them, / they are somewhere else. / But someone pays the police. We do. / That we are meant to believe the poem can say moon / but not government.”

Driving back and forth to the lake, I read signs. They’re everywhere. Coolers at the ends of driveways with cardboard signs announcing Fresh Eggs $4/dozen. Farmstand sizes of many shapes and colors: Fresh Tomatoes. Sweet Corn. At the corner of Greenfield Road and 112, a lawn sign advertising the Heath Fair. My favorite is the hand-painted sign above a beautifully constructed roadside cabinet (it looks like a Little Free Library) that says SOAPSTAND. Inside, homemade goat milk soaps. I drive through my landscape and read the signs like notes. Signs as notes telling me where and when I am. Telling me what’s here, what’s hidden, what’s coming.

This fault line, this animating question, this shape of we. This space between body and body, earth and earth. In every collection I read this week, it hovers, it sings, a sounding note. Joy Harjo, from the afterward to “The Myth of Blackbirds”: “Being in love can make the connections between all life apparent— / whereas lovelessness emphasizes the absence of relativity.” Ari Banais, from “Being With You Makes Me Think About”: “We is something like a cloud. How big, how thick, / its shape—ambiguous. We is moving across / a magnificent sky.” Etel Adnan: “A tree is always courageous. By the way, we’re just a window on the world.” I take the question into my body into the world.

In the epilogue to This Wound of a World, Belcourt insists that “love is a process of becoming unbodied; at its wildest, it works up a poetics of the unbodied.” A poetics of the unbodied. It stuns me. It is, I think, one of the places I am trying to go. He goes on: “That indigeneity births us into a relation of nonsovereignty is not solely coloniality's dirty work. No, it is also what emerges from a commitment to the notion that the body is an assemblage, a mass of everyone who has ever moved us, for better or for worse.” I’m thinking about trees, their relationships with fungi, their relationships with each other. I’m thinking about the bodies of fungi, how they travel. I’m thinking about how the forest is kind of unbody, how it might be a model for how to unbody in the right direction, the direction that brings us closer but doesn’t collapse us into sameness.

Then, this world-shifting paragraph, also from the epilogue: “If I know anything now, it is that love is the clumsy name we give to a body spilling outside itself. It is a category we have pieced together to make something like sense or reason out of the body failing to live up to the promise of self-sovereignty.”

Isn’t a forest simply a body spilling outside itself? "Can’t you relent, can’t you love yet / your small bewildering part of the world?”

I wrote a cento composed of lines from the seven collections I read this week. Here it is, for you:

Perhaps This Is What Being Medicine Feels Like

Every time I walk beneath a tree,

I find something to love

in the world’s rich dirt.

Nothing older than grieving.

In this night, all nights,

I set a table for the wounds

to world inside.

Here comes the word for mystery.

Adoration: am I not yours?

One day I will open up my body

to give to shapelessness

time to quiet down. Beauty

at last nothing but a muscle moving.

Grief rattling around in the bowl of my skeleton

has fallen in love with everything.

We are a small earth.

We will be dust together,

in the ground, in a field,

in the wind. A thing

this season makes and unmakes.

We are tangling without touching.

We return home, in tears.

A body

is a place to keep loss

or its consequence of light,

to become

and unbecome

a language that, all this time, we knew.

We is moving across

a magnificent sky

toward the nearest star.

Thanks for reading, friends. If you’d like to send me a note from your week—a nourishing one, a sad one, a confusing one, a silly one—I’d love to receive it. You know where to find me.

Reply